Many of us have been using the events of 2020 to justify many of our undesired and unhelpful behaviours. Undoubtedly, it has been an emotional and uncomfortable few months but I have news for you – that’s not the reason you are off track.

It’s not a virus’s fault that you have been baking with flour, sugar and butter incessantly for 3 months now. It’s not the desperate need for racial equality that is driving you to drink more alcohol than you usually do. It’s not even the fear of paying for gyms and studios when money is tight (even if they weren’t closed) that is causing you to skip your workouts. It isn’t any of that stuff. That is just the window dressing. Those are scapegoats.

The real issue is that we have never been taught the correct way to address uncomfortable feelings.

We are suddenly bored of being cooped up at home. We are either ashamed of our heritage or enraged by it. We have had our jobs and finances upset and find it scary and difficult to establish new avenues. And all of this makes us fall back on the habits that we have practiced during previous times of discomfort.

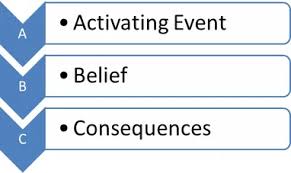

You may have heard this referred to as the “think-feel-act cycle.” Or, in Cognitive Behavioural Terms, it is the ABCs.

The ABC model was created by Dr. Albert Ellis, a psychologist and researcher and its name refers to the components of the model:

A. Adversity or activating event.

B. Your beliefs about the event. This involves both obvious and underlying thoughts about situations, ourselves, and others.

C. Consequences. This includes your behavioural or emotional response.

When C (the consequences) turns into a destructive or even an undesirable behaviour (like overindulging or skipping your workout) instead of rushing to the baking cabinet, I suggest that it is time to look at B (our beliefs) instead. I mean, let’s face it, we really have no control over A and waiting it out is taking a lot longer than we had initially hoped.

In this ABC model, B is considered to be the most important component because if we can identify the belief that isn’t serving us, we can question it and ultimately change it. And once we change that belief, we change the consequence.

Here’s an example:

- your spouse brings a bag of donuts into the house (that is A).

- You see the donuts and think “Oh no, I am trying to lose weight but when I am this stressed out I am not able to resist the deliciousness of donuts.” (that is B).

- You hold off for a while but eventually snap and eat not just one but a few of the donuts (that is C). Then you are mad at yourself, your spouse and the scapegoat of “2020” gets the blame.

So, you can see how changing B is a lot easier than changing A (you can’t control someone else’s behaviour – not for long anyway) and C is a direct response to B. So what are we left with?

Doing some deep questioning into the validity of B.

Are you really powerless around donuts? Are donuts really that delicious? Even if they are, do you have to eat them, just because they are there? Is the momentary reward of eating a donut more satisfying than making another step toward your goal of weighing less? Is blaming your spouse for bringing them into the house going to solve this issue? Is getting upset with yourself for not having more willpower going to prepare you for when this happens again?

By asking yourself these (and other) challenging questions, you can eventually rewrite the narrative of this ABC, and every other ABC, into a story that helps you achieve your goals rather than derailing you.

This is the type of game-changing work we do in the Weighless program that no other weight loss program does. Doing thIs deep work of cutting the issue off at its source, makes calorie counting and food tracking irrelevant.

It starts with being aware there is work to do – and ends with doing the work. And that work is forever. Not just until you have hit your goal weight.

So, are you willing to dissect and examine your ABCs?